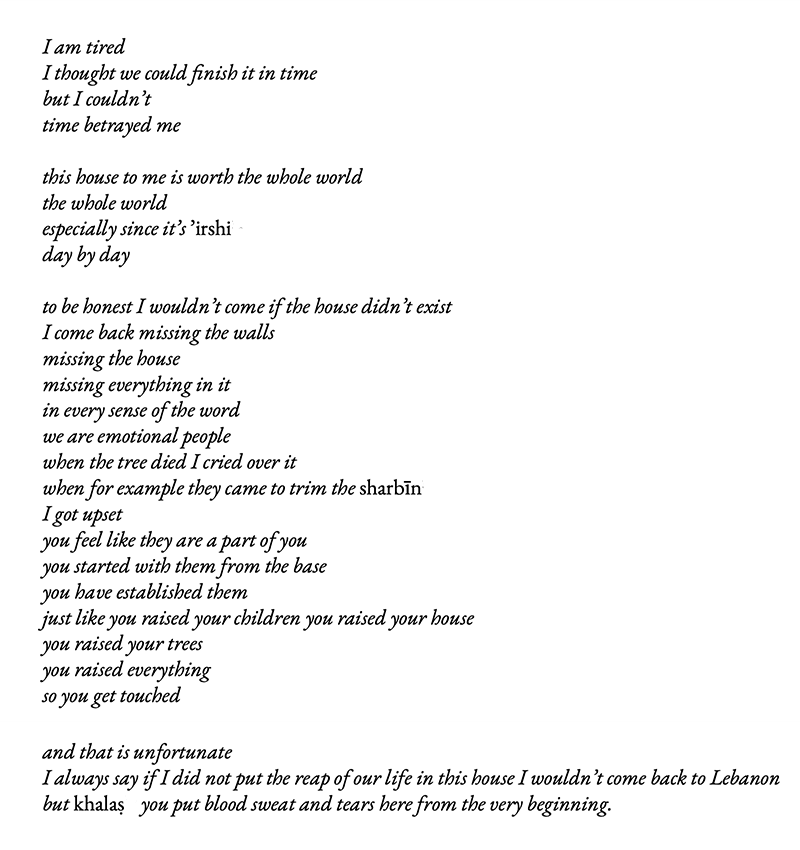

Sа̄mia is leading a tour of her house as she tells me how it was brought into being. When we reach the initially-intended main entrance of the house, she declares:

The key is not in its usual hiding spot—the gap between the wooden door frame and the concrete blocks. It is

left hanging from the door’s lock as if waiting for us to enter.

Three years after laying out the foundations for a house in her village, Sа̄mia continues funding the construction

of the rest of the structure. For the next stage of the house’s development, she chooses contractors she trusts: her friend from the village oversees the structural concrete work, and her friend from Qatar, who moved back to Lebanon, is in charge of the stonework. Although an architect is involved, his role is mostly relegated to the

paperwork needed to apply for a building permit, and the house is designed as needed, as progress is made. For

instance, to frame the mountain views Sа̄mia wants from her home, the architect draws and describes an arcaded

terrace to the contractors on the spot, leaving them to fill the spaces between the cast columns with cinder blocks

and then cut and grind them to a semi-circular outline.

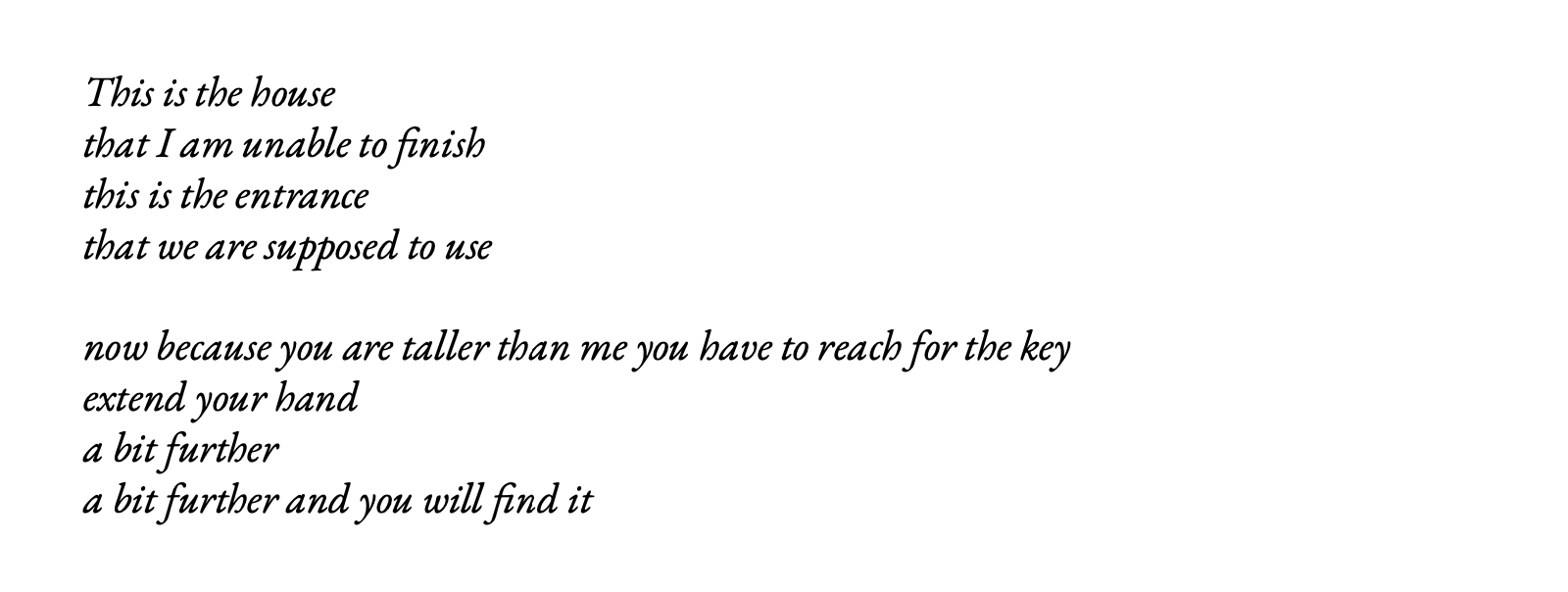

Although covering the exterior walls in stone is not a priority considering the rest of the house is still bare—

in exposed concrete—Sа̄mia had saved $8,000 over a full calendar year to be able to clad part of her house’s

elevation. So, because she spends the majority of her twenty summer vacation days in Lebanon outside, she

prioritizes covering the walls visible from the street and those surrounding the ground-floor arcaded terrace.

Going for inexpensive materials or partial improvements serves her well: the faster she completes construction

within her financial ability, the sooner she can occupy and enjoy her home.

![]()

Although Sа̄mia has a cohesive vision for her entire house, she no longer intends to complete it in full.

Construction began strong and steady, but it will take longer to, and maybe never, conclude. Sа̄mia lost the

savings she deposited in Lebanese banks after the currency’s steep devaluation. She also lost a percentage of her

monthly income after the blockade on Qatar,Javed, “The Qatar Blockade’s Impact on Migrants,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

where her family has been, and still is, living and working for

twenty years. For diasporic subjects, budget and the built form is affected by multiple locations’ political and

economic situations. While cladding the rest of the exterior walls in stone is still part of Sа̄mia’s scaled-down

ambition, the change in her financial capacity affects her expenses and, by extension, her choice of materials:

half of the façade will be clad in the hammered stone tiles that Sа̄mia likes. In contrast, the rest will be clad in

cheaper, smooth stone tiles.

![]()

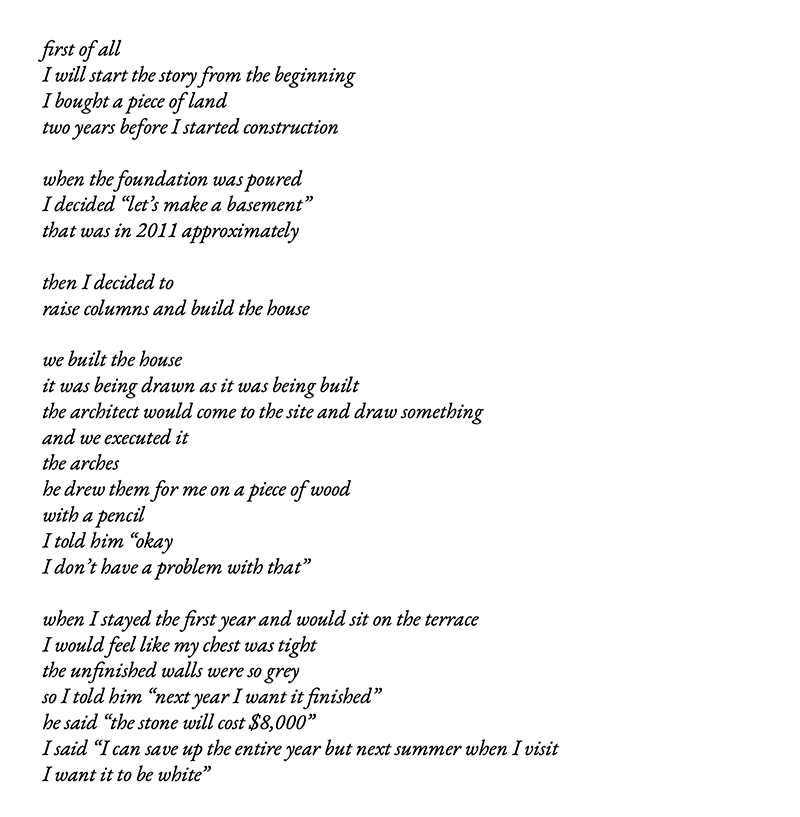

Installing the untextured stone costs $70 per meter squared, therefore, Sа̄mia portions the façade’s surface area

to help approximate the wall that can be covered with the amount of money she has. And because the entrusted

stonemason, like the rest of the locals, does not believe in and, by extension, does not deal with money via local

banks since the liquidity crisis,Gebeily, “Cash Is King in Lebanon as Banks Atrophy,” Reuters. money transfer is the payment method of choice. In diasporic homemaking,

remittances have implications on the built form: the next guiding factor for Sа̄mia is the amount of money per

Western Union transfer that she accumulates and sends to the stonemason. So, with every $1,000 she transfers

from Doha to Shūf—where there are already three Western Union agents in her village alone“Find Locations – Western Union,” Chouf, Lebanon | Western Union.

—she can cover

14.28 meters squared of a wall.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Sа̄mia’s expenditures account for the costs associated with wire transfers. In these transfers, where the money

is sent is the stable reference point of Sа̄ mia’s home, which receives the fruits of her labor. And the place where

migrants send money from is often fluid and changes based on economic opportunities. Diasporic subjects

consider these fluctuations: estimates of construction costs include transaction fees, which depend on the

sender’s location, the amount of money, and, over time, the number of transfers needed. Some methods are

expensive, costing more than the $20 fee per every $1,000 that the sender accounts for, but can be cashed out

within a couple of hours to a couple of days. Other service providers’ fees are cheaper, but transfers take longer

to arrive. Finally, service providers are chosen based on their proximity and accessibility to the receivers.

This year, Sа̄mia attempts to proceed with the construction without breaking the bank. Since in the winter,

she experiences her snow-covered home via WhatsApp pictures, Sа̄mia does not install any heating despite

being located 1,943 meters above sea level. Sа̄mia’s family currently summers on the ground floor, which was

once intended to be the garage but now includes a kitchen, a living room, two bedrooms, and a bathroom. To

prudently gain more space, she proposes to expand, albeit not fully, into the structure: the living areas could

move to the floor above, freeing up a room on the ground floor to allow her two children, who will soon be old

enough to go to college, to have separate spaces.

With every stay, Sа̄mia’s plans grow, but not to the full extent of her house’s existing structure. If business

abroad improves and the situation locally improves, she will adapt more rooms, as she did with the garage, and

move into them. In diasporic homemaking, “program”—which defines the space needed and the building

configuration early on in a typical design project—is contingent; it changes, adapts to, and shapes itself based on the availability of money and on the political and economic settings of “here” and “there.” Instead of

programming the totality of a design object, diasporic subjects like Sа̄mia can live in fragments of a house that

can accrue over time. During the long periods it sometimes takes to complete a project, changes in finances allow

the house’s program to shrink or expand, for ideas to be revised, and for new ones to emerge.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In Sа̄mia’s home, the main entrance where we began the house tour is the physical threshold that separates the

clean and occupied parts of the house from the incomplete house. In front of the main entrance that is to the

side of the building and away from the street, the terrace, and the garden with fruit-bearing trees are piles of

gravel, bunches of rebar, boxes of materials samples, and wooden templates used to create the concrete arches.

But just because two floors are in exposed concrete and cinder blocks, doesn’t mean Sа̄mia does not use them

nonetheless:

Sа̄mia occupies the space of her home imaginatively: the future programs of the house, in this case, the balcony

of her salon, still fulfills its function. By setting aside the tension between the reality of her home from her

imagined home, Sа̄mia resists deferring experiencing the house and the moment of peace it offers her when she drinks her coffee overlooking the Cedar’s Nature Reserve. For diasporic subjects, the distance between the intended program of a space and the actual program in place occurs simultaneously: while we tour the

unfinished floors, Sа̄mia refers to the empty rooms as a kitchen, pantry, office, guest room... Even the ground

floor is interchangeably called “the garage” and “the living room.” Sа̄mia’s optimism of one day living in her

dream house, and insistence on moving forward in the construction without knowing what is next or what

the end might look like, mirrors what many migrants feel when they move from one space to another without necessarily knowing whether a possibility might eventuate.Hage, The Diasporic Condition, 43.

Sа̄mia’s perseverance

to make progress, even if it is incremental, is the reason her house is ready, albeit partially. Concomitantly, the

house itself contributes as a force propelling her to move forward: it is the reason she travels back to Lebanon.