The swing I am on squeaks faintly as wind rushes across the valley before us. Opposite me, seated under the

shade of a juniper tree and with this panorama as his backdrop, sits Mа̄lek. He is already speaking before I can

manage to get my sketchbook out.

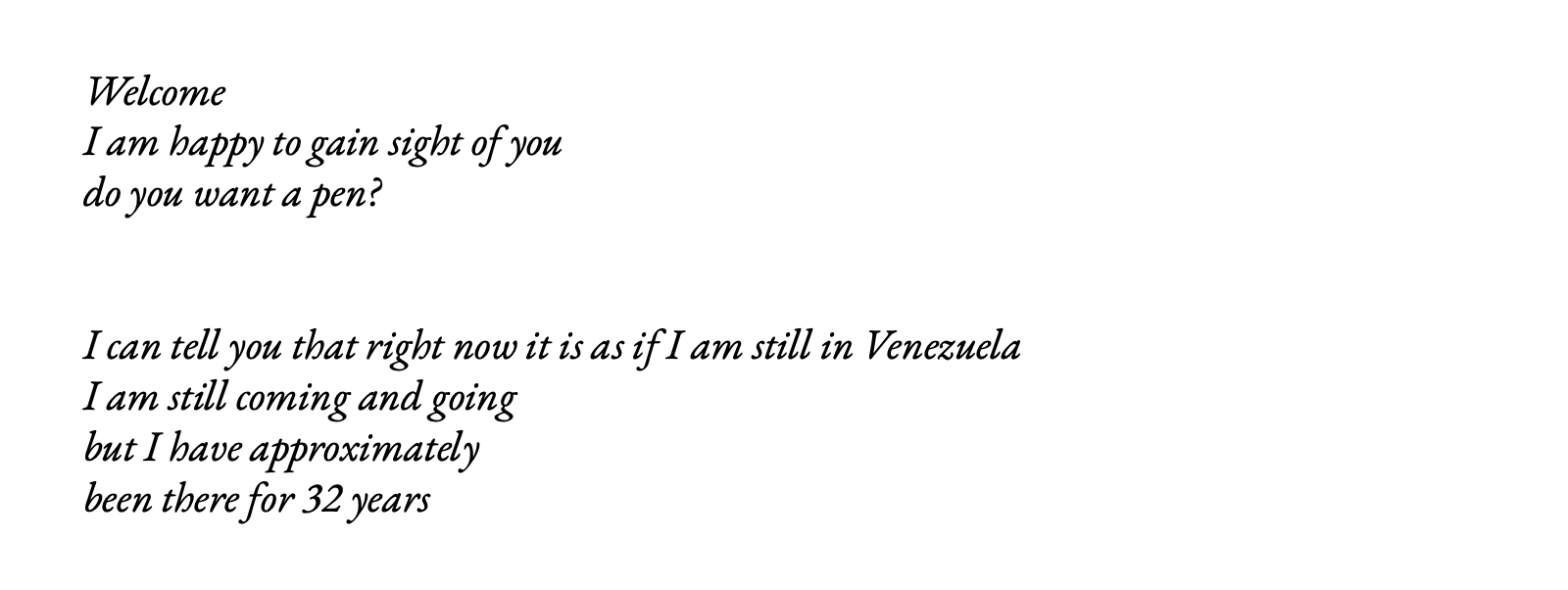

Mа̄lek recounts his travels in between quick sips of maté. Eventually, he emphasizes that we owe this garden-gathering to his father.

![]()

![]()

It was just after Mа̄lek had moved to Venezuela as a young adult to work for his maternal uncle that his

stonemason father, Mа̄lek senior, convinced him to build a house of his own in their village. Erected on

inherited land, right next door to his parents’ house, Mа̄lek house is partially clad in burnished white

limestone and capped with a pitched clay-tiled roof. The entire property is lushly planted. While the house

blends inconspicuously into its context, the reasons for its very existence and the way it was brought into being

are completely at odds with greater village life: the home was conceived across years of letters and remittances,

exchanges that connected father and son, home and abroad, across a network of trusted messengers. During

the two decades it took to complete most of the construction, several community members became involved,

contributing to and later taking over the homemaking process after Mа̄lek’s father died. Together, they joined a

diasporic culture without having even migrated.

Although Mа̄lek had geographically left Lebanon, the house maintained a presence on his behalf back home.

The money and messages he relayed to relatives, the visits he planned to check on construction—such was the

common milieu that Mа̄lek and his family members came to share through the space of the home. Their joint

lifeworld transcended spatial distance

and constitutes the diasporic conditions that permits Lebanese migrants

and their families to establish themselves abroad while remaining socially, economically, and politically related to

Lebanon and to each other.Hage, The Diasporic Condition, 11.

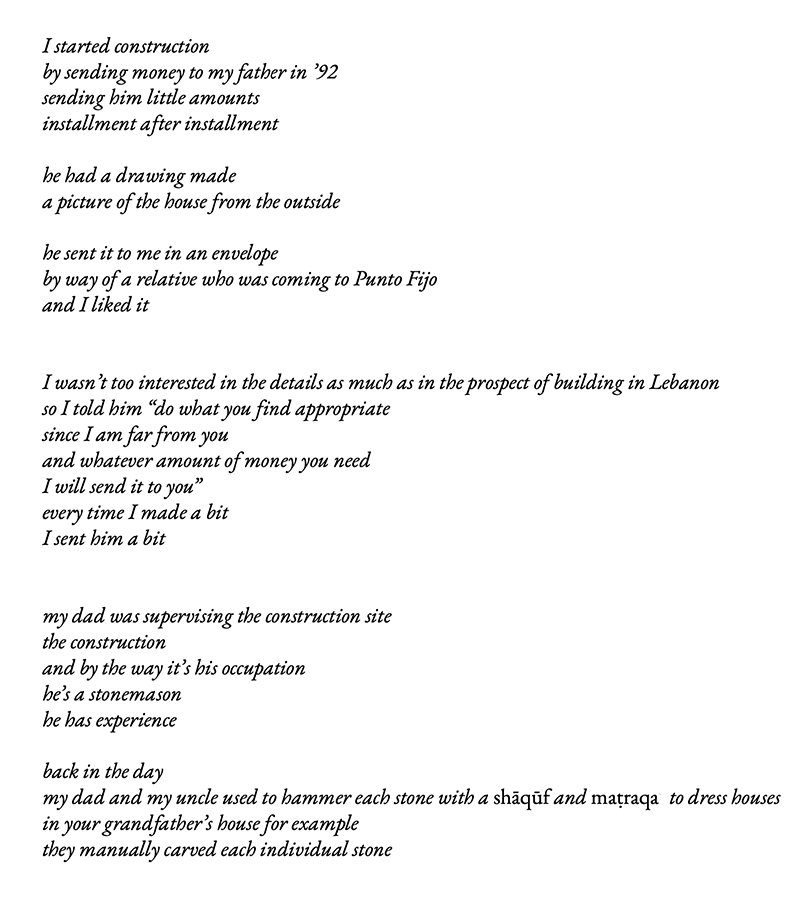

Mа̄lek’s continued interest in his homeland and connections to groups overseas challenge usual immigration-

speak, which articulates an opposition between stasis and movement or between here and there.Hage, The Diasporic Condition, 44.

The desire for

moving in the world and the desire to remain and valorize home are often presented as two opposing forces that

act upon, push, and pull diasporic families; Mа̄lek is able to reconcile this duality. This reconciliation, termed

“diasporic lenticularity” by anthropologist Ghassan Hage, is a condition where diasporic subjects fulfill both

yearnings and inhabit multiple realities rather than being torn between them. The word “lenticular” alludes to a visual process, like that of a Tabula ScalataA Tabula Scalata, Latin for “ladder picture,” is a picture where two images, divided into strips on different sides of a corrugated carrier, can be viewed correctly from a certain angle. When the images are arranged vertically, the picture seems to change from one image to another while walking past it., where photos intrude on one another according to the angle of vision of the viewer. The relational connection between what is visible and the viewer’s location mimics the flickering that diasporic subjects experienceHage, The Diasporic Condition, 94., which oscillates between existing in Lebanon and in the land to which they have migrated.

![]()

![]()

After a long silence, Mа̄lek excused himself. I could tell the conversation was over. By then, his wife Jinа̄n has

joined us, and she takes one last chance to say how grateful they are for their home.

Mа̄lek and Jinа̄n returned to Lebanon when Venezuela’s socioeconomic crisis violently devolved in 2011.Cawthorne and Wallis, “Venezuela’s Chavez Devalues Bolivar Currency Again,” Reuters. But by 2019, Lebanon too plunged into an economic crisis of its own, with a sharp drop in the value of the

Lebanese pound triggering a domino effect of rising inflation, the government defaulting on its public debt,

unemployment, and a shortage of fuel and other key imports. For Mа̄lek’s family, two local consecutiv crises, miles apart, compounded the family’s personal instability. Today, it is their home—what once elicited

daydreams, kept them in touch with friends and family, and created reasons for travel—that is their base, their

refuge in a global network of re-migrations.