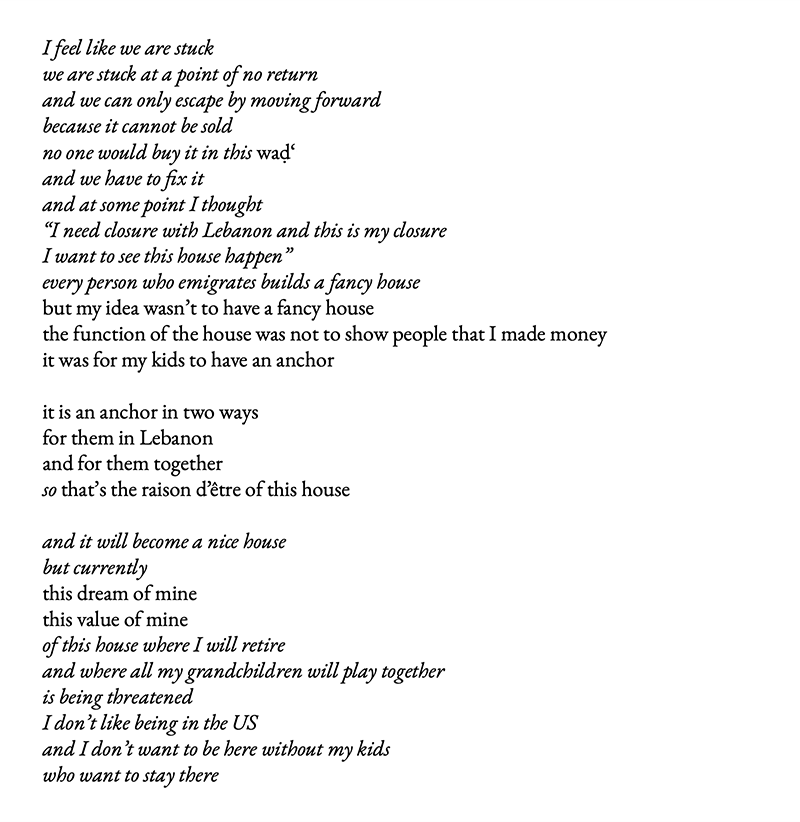

Līzа̄ and I are sitting in her car, parked across the street from the house she is describing to me. Usually, she says,

she prefers to avoid the neighborhood—the location of her and her husband Jа̄d’s renovation project—for fear

of disappointment.

![]()

![]()

Although I cannot see the entire house from the car’s window, Līzа̄’s descriptions of it are vivid. I find

myself able to mentally fill in the blanks: it is a three-story stone-clad structure with an arcade overlooking an

untended garden. Built in the 1950s, Līzа̄ and Jа̄d had to ask, search for, and seek out the owners, who are based

in France, for ownership of their abandoned house. When an agreement was reached, the structure was passed

on from one diasporic family that had renounced its attachments to Lebanon to another family looking for a

home base in their homeland.

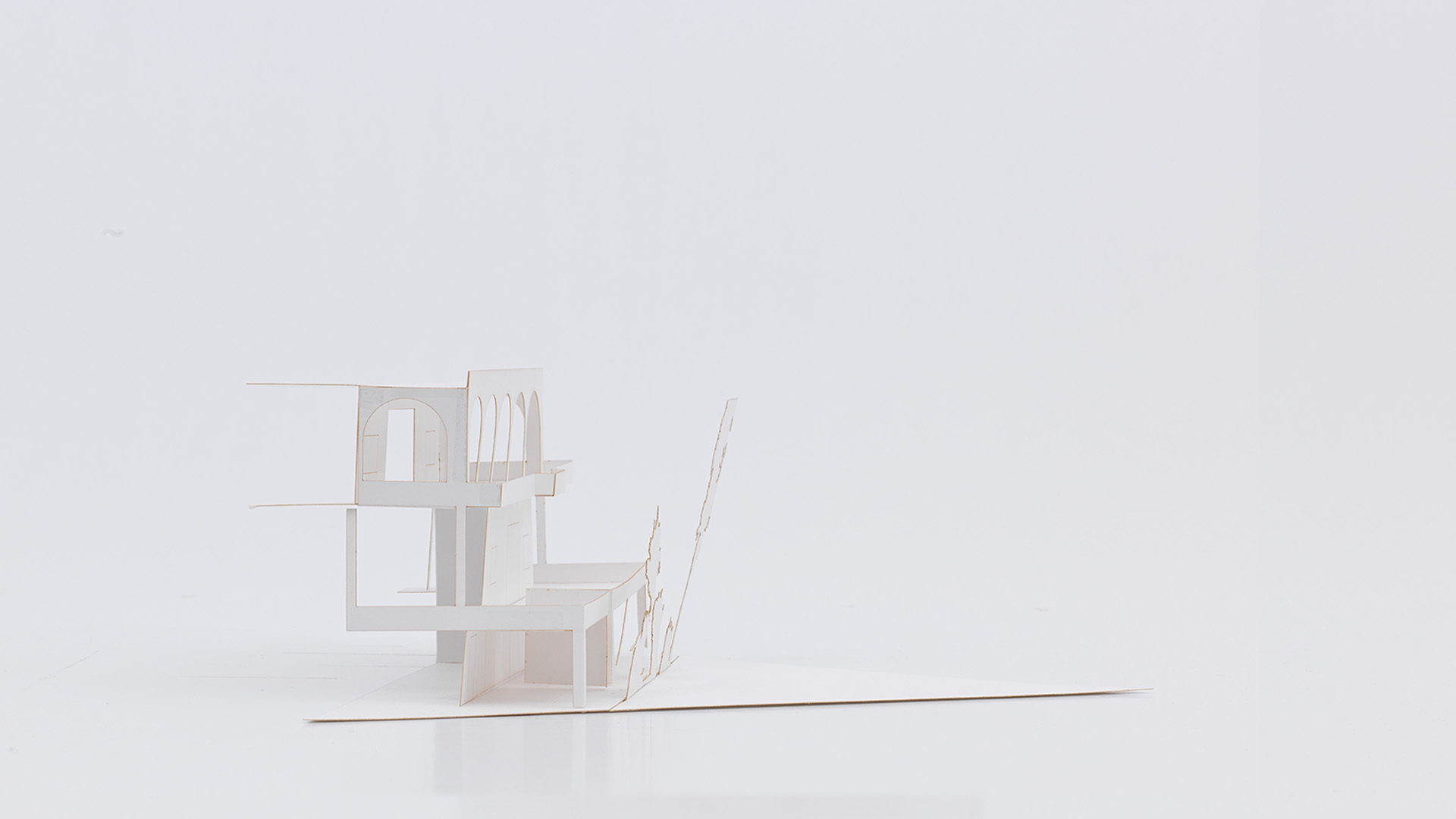

Since becoming the homeowner over a decade ago, Līzа̄ has had many ideas for the renovation. Her original objective was to fix the entire house: she and her family planned adaptations for all the floors and the garden.

They even dug out a shelter underneath the ground floor to hide from any shelling in case of political instability. Unfortunately, that plan proved too ambitious. As a second, more manageable step, she and her family resolved

to focus on fixing just the ground floor in time for the summer holiday. But that too did not end up working

out. Coordinating the logistics from afar and with a busy schedule proved too difficult. When she had built up enough energy to try renovating the third floor—the floor with the arches that Līzа̄ loved, that also came to

an untimely end. Other unsuccessful ideas over time included excavating the garden and building a basemen to house an art studio, or adding one more floor to become an entertainment space to accommodate her kids’

musical instruments—a piano, a drum set, and a ‘ud and guitars’ corner. In 2014, the renovations were

halted altogether to pay for their children’s university expenses. And in 2017, repairing it was even further

out of reach when the family began planning a second immigration from Saudi Arabia to the USA.

![]()

Considering Līzа̄’s family is in the midst of settling in a new country, there is a possibility they may never live in their homeland house. Yet, about a year ago, she and Jа̄d decided to resume renovations with a more realistic

timeline in mind: hold off on fixing the three existing floors, which will be willed to their kids, in the hopes that

they may someday renovate them on their own, and take advantage of a new building code that allows emigrants

to add an extra mezzanine floor to their residence. The latter was written into law to generate capital from the

country’s widespread diaspora in the midst of an economic crisis: the lira has lost over 90 percent of its value,

nearly 90 percent of the population now lives beneath the poverty line, and fuel and electricity shortages are

dire. Only the superiority of the currency they accumulate abroad—that of the Saudi Riyal to the Lebanese

Lira—helps keep them afloat now. This arbitrage of currency is the primary lifeline for most other families across

the country too.

In total, Līzа̄ and Jа̄d have rethought and reconfigured their house, in plans and daydreams, about seven times:

they moved from potentially living on all three floors to just the ground floor, to just the third floor, and

finally, just the to-be-added mezzanine. Such is hope, that which ebbs and flows between ambition and reality,

investment and inflation.

To expand the structure and build the mezzanine that will become their maybe part-time, maybe full-time,

maybe never residence, they hire two contractors—who are also relatives—to begin extending structural

columns and building the walls. Jа̄d is updated on the project as progress is made via WhatsApp. In a group

chat on the instant messaging service, he is the “administrator,” and the “participants” are the foreman, concrete

foreman, and stone mason. All three have to coordinate since the construction detail, replicating that of the

existing house, requires building concrete and stone in conjunction.

Although casting the concrete with the stone as one wall element takes longer than a typical concrete wall clad

with stone, the instantaneity of WhatsApp communication affords their family time: they don’t have to be

physically present for construction to progress. Instead, Jа̄d can experience the site despite geographical distance

through a picture fragment on his phone. He annotates images, zooms in for close-ups, and crops and annotates

some more to communicate ideas, changes, and next steps through messages. Instant updates from people back

home, within easy reach on his cellphone, allow Jа̄d to hear about parts of the project that wouldn’t have been

mentioned in a once-a-week phone call. Besides, calling internationally is a costly affair for both Jа̄d and his

connections in Aley, so they prefer to send text messages and make phone calls for free over the Internet.

In Lebanon, more than two million people regularly use WhatsApp. In fact, the protests of fall 2019, or the

“October 17 Revolution,” were in part prompted by a proposed tax on the use of the messaging platform

WhatsApp to raise revenue for a state with no reserves and have since turned into a broader call for rebuilding

the nation’s political and economic system.Mordecai, “Protests in Lebanon Highlight Ubiquity of WhatsApp, Dissatisfaction with Government.” Pew Research Center.

This flow of communication is part of the majority’s daily routine.

In the absence of physical proximity and with a far-reaching diaspora originating from the country, it is an

essential form of communication that keeps families and business partners together and connected.

In diasporic homemaking, as for Līzа̄ and Jа̄d, diasporic subjects experience their houses abroad through

WhatsApp as extensions, not substitutes, of a place. Architecture often naturalizes the relation between

building and site, assuming that “site” is location, simply where the building is bound by its coordinates. But

diasporic homemaking destabilizes what we understand by a localized residence and challenges the conception

that to be somewhere, a person must remain situated in one place at a time while remembering and invoking

another. For diasporic subjects, multiple realities collapse, where they can be on-site without being physically

there. To homemake from abroad is also to occupy multiple places at once. It is to be situated in both spaces

simultaneously without having to move between them.

Months after speaking to Līzа̄ in person, I follow up with Jа̄d over the phone, to check-in on the progress of

mezzanine floor.

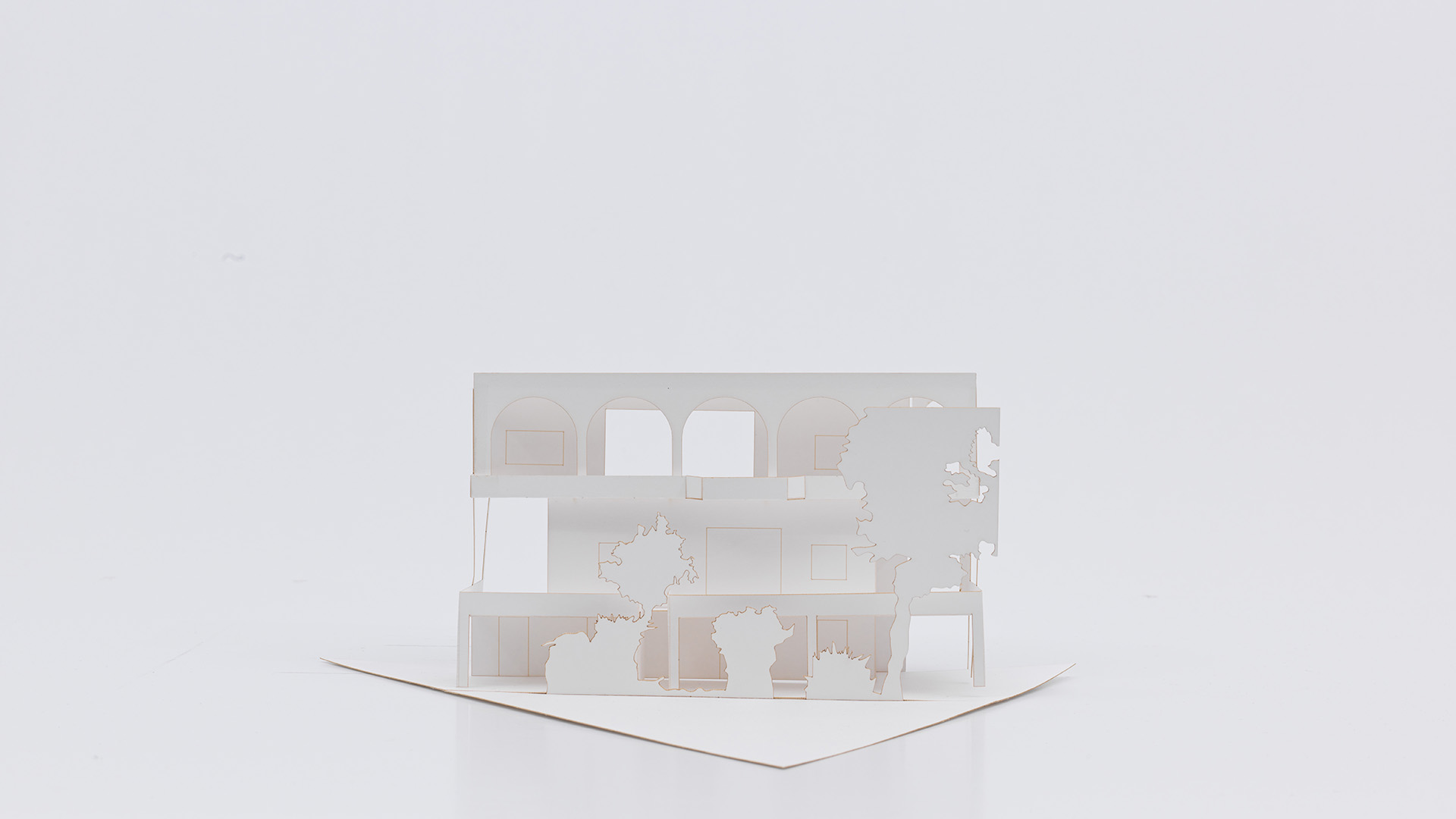

Traveling to make sure that the rebar details are without error before casting the concrete is not the only in

person visit Līzа̄ and Jа̄d made to the house. When they are told about a house in the process of demolition,

whose stones originate from the same quarry as their own house, they fly from Riyadh to Aley to make sure the

stones’ color really does match. They travel with $7,000 in their suitcase—Saudi Arabia restricts $16,000 as the maximum cash you can transport while crossing international borders.Shaik, “Cash Limit Allowed to Carry at Saudi Airports,” Saudi Expatriates.

The site, previously fragmented and

dispersed throughout messages, now converges with an in-person visit to the house. Once there, Jа̄d and Līzа̄

get to cognize discrepancies between what is captured in the images they receive and the structure itself:

sometimes, what they see in an image does not match up to their expectations, and other times, they get

to see what has been kept outside of the camera view and the picture frame. In the process, the site visit

oscillates between disappointment and satisfaction; either they are happy with, accept, or change what has

already been built.

![]()

![]()

In regards to their own home, Līzа̄ and Jа̄d are happy to see the arches of their mezzanine floor come to life,

matching the outline of those below them. Yet the picture they had received, taken facing one side of the

building directly, did not show that the arches of the mezzanine and those of the third floor are of different

thicknesses. Although they could dictate the shape of the arch via WhatsApp, they could not control its depth,

its three dimensions at once. In diasporic homemaking, a site visit reconciles what subjects had assumed and imagined with what is physically there. Instead of checking progress, and measuring dimensions and comparing

them to pre-existing drawings, subjects discover the conditions within a picture and what is beyond a camera’s

sensor frame in real life. The space outside of the camera lens becomes a margin for tolerance, either a space of possibility—where control is only bound to the fragment of media communication we receive—or of

incapability.

Currently, Līzа̄ and Jа̄d’s extension is on hold: a months-long ongoing strike led by municipality employees is

halting the approval of their extension, and they want to save to buy a house in the United States. The stones

they purchased lay in the garden of the house until they are ready to resume renovations. If the US housing

market improves and becomes more affordable,Richardson, “2021 Housing Market Frenzy Concludes with Double-Digit Price Growth,” Forbes.

they might go back to fixing the third floor, the one with the

arches.